Luka’s Scoring

There was plenty of intrigue in each and every corner of the 2019-20 NBA regular season, so I admittedly missed out on some of this season’s biggest stories. One of those, unfortunately, was the explosion of Luka Doncic, who fresh off his ROY award averaged an absurd 30.5/9.9/9.3 per-75 split while quarterbacking the best-ever NBA offense (based on ORTG) as a side-hustle. His passing talent is obvious, but given his perceived lack of physical tools, it’s remarkable that he’s able to create enough advantages not only to capitalize on his vision, but to score 28.8 points a game on a 76th-percentile 59.5% TS. I wondered how, without premier speed, quickness, strength, hops, or shooting, he was able to hold up his side of the bargain in the Mavs’ heliocentric offense. He’s obviously surrounded by a great complementary roster, but Dallas’s roster only amplifies what Luka does best. Anyway, let’s start getting into his scoring game by looking at everything that makes it great.

Why?

Part of what makes Luka’s scoring so great - and generally, what separates elite creators from low-ceiling volume scorers - is simply context. One half is that due to Luka’s unselfish nature, very few if any of his shots will come at the expense of a better one; the Mavs’ scoring efficiency when Luka is on the court is on par with Luka’s himself. The other is that most of his looks are self-created, as he literally has the lowest ASTD% among wings at a measly 19%, so he really doesn’t rely on others setting him up, although how Luka can/will scale up is yet to be seen. Ultimately, the fact that Dallas finished the season with the highest offensive rating in NBA history is probably enough to tell you that Luka’s numbers are impactful, not empty.

How?

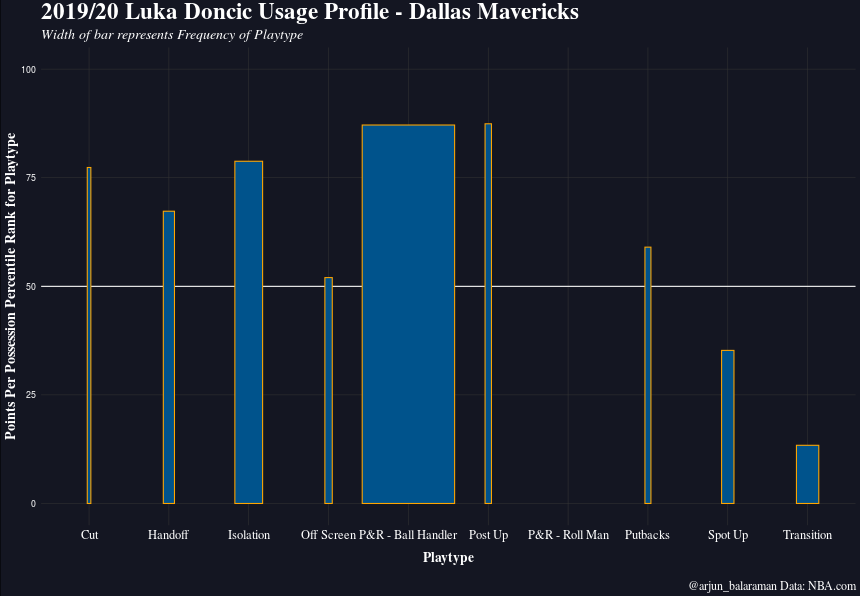

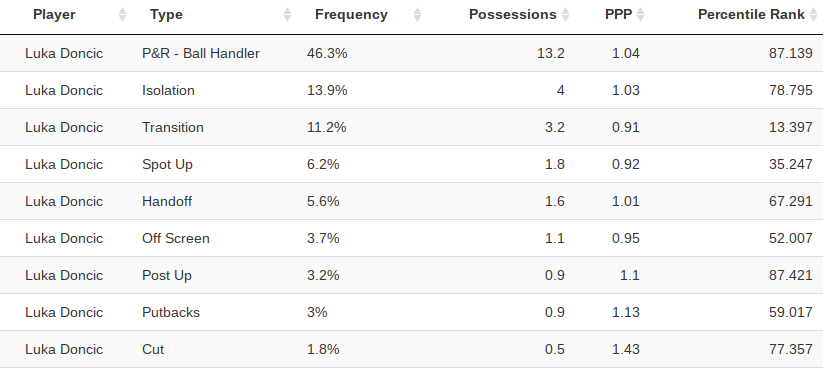

“How?” was the first thing I wondered when confronted with Luka’s scoring, but specifically how he created a bountiful of advantages each game. As a heliocentric centerpiece, I think it’s very important that we understand the game context in which Luka creates and capitalizes on his advantages. Here is his playtype usage profile (the tool I used is arjb10.shinyapps.io/radialplots/):

As you can see, the pick and roll is Luka Doncic’s bread and butter. The 1.04 PPP he averages (which only counts plays that he finishes w/a shot attempt or turnover) is incredible half-court offense, especially when you consider the volume he sustains. Now, let’s take a look at what makes him so great in the pick and roll.

(quick note: Before the Clippers series, I assumed that Luka would struggle a little in his first postseason going against a top-5 defense, but a multitude of factors, some under Luka’s control and some not, proved me dead wrong, which is part of the reason why I decided to write this.)

Here, Luka faces off against the NBA’s favorite P&R coverage, the drop, where the on-ball defender goes over the screen and the big man drops back; this scheme hopes to deter any looks at the rim and instead force the ballhandler to take a pull-up 2 while the screened defender recovers. This is where Luka shines. One would think that a slow, earthbound player might have trouble attacking the rim in these situations; instead, Luka gets high-quality shots. How? By going even slower. While not commonly thought of as an athletic attribute, deceleration is still a physical trait that can be used to create advantages. Thus, Luka is able to lose Harrell by halting his forward momentum on his last step, getting the easy floater.

In the first clip, Luka rejects the screen after drawing Morris slightly towards it with his first cross, opening up a tiny bit of room for his drive (notice how he’s not able to just blow by Morris). He drives with the bigger Morris smothering him until it’s time to release the ball, when Luka then rises up in place as Morris helplessly falls backward, giving Luka a clean shot at the rim. In the second clip, Luka decelerates and uses his body to outlast Paul George’s help. The main takeaway from both clips is how Luka utilizes his body as a shield, protecting the ball and concealing his shot trajectory until the very last second, where he re-orientates himself towards the hoop and rises straight up for a now-open look at the rim. This is Luka’s most effective tool when matched up against bigger wings, not unlike Morris and PG. (In the second clip, notice how Zubac is about to drop back and defend Luka until he realizes that Kleber, his man, can shoot the 3. Shoutout to Dallas for putting a well-fitting roster in place.)

Another example of Luka’s remarkable deceleration. It’s probably not necessary, but these clips are just too aesthetically pleasing to resist. Here, the Clippers are playing without a traditional big man on the floor, and they switch the P&R, leaving Luka with Pat Bev. There’s no one waiting for him in the paint, and Luka successfully loses Beverly en route to an easy layup. And just as a reminder, Luka relies on his arsenal of tricks to get breathing room at the rim.

Here, Zubac is more thoughtful, playing along with Luka instead of trying to beat him to a spot. This is when Luka’s lack of explosion shows; Zubac doesn’t take the bait, and Luka struggles to finish with a big right in his face, something that’s a significant trend for him (however, it’s important to note that he does well in avoiding those scenarios entirely - 6.61% of Luka’s rim attempts were blocked this year, about the same rate (6.45%) for the Greek Freak). However, Luka still has another trick or two up his sleeve reserved for these types of situations:

(Here’s the first appearance from a clip outside of the Clippers-Mavs series)

As you can see, he adapts to a lack of space by keeping his dribble alive and coming to a stop, where he can use his 6th sense (timing/awareness) to get a shot off while the big is off-balance.

Now, let’s take a look at Luka’s other core P&R tool, his seal. Luka’s incredible feel for where everyone is on the court combined with his solid frame help him execute seals. For those who are unfamiliar with the term, sealing is when you dig your body, specifically your gluteus maximus, into the defender behind you, ‘sealing’ him off (another common term is ‘putting your man in jail’) from the play and creating a quick man advantage. It looks like this:

Here Luka seals off perhaps the most dangerous perimeter defender in the league. Notice how as he feels Kawhi shift from behind his left shoulder to behind his right, he crosses over accordingly, prolonging the time that Kawhi is ‘in jail’. Once Harrell commits to him, Luka flips it to Boban for the easy dunk. Lou Will can’t help, not only due to he and Boban’s height discrepancy, but also because Luka is all-seeing. A similar situation plays out below:

This play happens a lot quicker, but it follows a structure similar to the last one. Luka has his man behind him; Zubac, the big in this scenario, zeroes in on Luka, but the difference here is that the strong side corner defender, this time Morris, decides to step up and cover Finney-Smith’s roll, so Luka wastes no time in whipping a pass to the corner for a 3. Luka’s ability to create and execute in these scenarios vs a drop coverage is scary good. The drop scheme hopes to force a mid-range jumpshot, but Luka’s vision and patience consistently find a better look. Even when he isn’t shoving himself right up against his man, he virtually always buys extra time and space by curling around the screen and gravitating towards the middle of the court, prolonging the recovery of his primary defender.

I really liked this clip, because not only does Luka relocate towards the middle well, but he’s one step ahead of PG’s swipe at the ball. Luka then delivers the lob to Kristaps, beating the 2v1. (Also to note - there are a couple of reasons why this play works as smoothly as it looks on the surface. In order to force the Clippers into a 2v1 situation in the paint, the Mavs have their other 3 players all on the left side, so that when Kristaps rolls to the right block, there’s no one there to interfere with the lob; also during the P&R, Kleber slides into the dunker’s spot, keeping Kawhi on him, and a corner shooter is the final screw that freezes the defense in place). Next, one of my favorites:

This clip beautifully exhibits the combination of Luka’s spatial and timeous awareness. First, he uses the screen twice, and it snags Simmons the second time around (notice throughout the clips how he generally maximizes the potential advantage to be gleaned from screen). Next, he seals off Simmons, waits patiently for Powell to roll to the dunker’s spot, taking Horford with him, and then lunges into the open space for an easy layup. That 6th sense carries over to other parts of his game, too, like this absolutely beautiful basketball play below:

Some off-ball chops are a nice sight, especially when thinking about how to build a contender around Luka, and who in many ways is very similar to some bearded guy in Texas.

Where?

As I kind of alluded to earlier, Luka is good enough and patient enough to more often than not get the look he wants. Below, you can see his shot distribution splits (data from CTG):

I should probably add some clarification here; the distances are as follows (in feet) - rim (0-4), short mid (4-14), and long mid (14+), and I ignored corner 3’s here, because he literally shot 14 of them all season. Also, while ‘mid-range’ probably triggers images of Jordan and Kobe, almost all of Luka’s ‘short mid’ shots are really just floaters and other one-legged touch shots (from what I watched, at least), so view it as an extension of his rim attacks/drives. Another way to capture his shot selection is by average distance: his average 2PA and 3PA shot distances are 5ft and 27ft, respectively, versus 6.5ft and 25.6ft league-wide. His accuracy looks like this (at the bottom is the % he shoots on that shot type while the y-axis is where that ranks as a percentile; stats per CTG and graph from app.rawgraphs.io):

As you can see, Luka excels at finishing; I’ve already detailed most of what makes him so good in the paint, and all I have to add is that he’s comfortable spinning both ways when going downhill, and can pull out a Luka-esque (translation: slow and calculated) Euro-step when necessary. All of his work inside adds up to a whopping 57.5% on all 2-point attempts, a stat which I think needs a little more love (small tangent time: yes, 3’s, layups, and three throws are the crux of efficiency, but it’s important to have numerous effective scoring paths - think of that Bob Meyers video you’ve probably seen - especially in the Playoffs, which is why I like to look at a player’s entire body of work, rather than nitpicking his strengths. 2P% won’t summarize any one skill, as Luka doesn’t have a 57.5% spot on the court, but rather, it abstractly sums up the total production you could expect from him inside the arc on any given night). This, in addition to 11.4 FTAs (w/75.6% free throw shooting, but that’s beside the point) per-100 rounds off a nice, efficient offensive game.

OK, now it’s time to talk about the 3’s. I have some mixed thoughts on them, and how you may address them depends on your perspective; from a player or team standpoint. Through the Mavs’ lens, I’d look for some secondary creation that could offer better alternatives to plays that end in a late, shot-clock-induced Luka 3, and maybe make a pull-up three or two, although those guys don’t exactly grow on trees. But this isn’t a Mavs breakdown. I totally understand that context matters; most of Luka’s 8.8, 31.1% three’s are self-created, and as a result draw reasonable respect despite being the lesser of many evils, in a vacuum. Because of Luka’s heliocentricity, I looked for any trends that could be concealing better shooting talent that can one day be expanded upon (other than the fact that he launches his average three from 27 feet; 0.4ft farther back than Harden, who plays a similar offensive role), and seemed to have found something. Breaking down his 3’s by time left on the shot clock, which could be a reasonable indicator of game context, some positive trends emerge (x-axis is 3PA, y-axis is 3P%, and dot size scales with 3PA):

As you can see, almost half of Luka’s 3’s (46% and 239 total) came during the 15-7s shot-clock range, when most NBA offense happens. Excluding possessions that came after offensive rebounds (where Luka took a negligible 29 3’s), the Mavs on average took 12.45 seconds to shoot (read: 11.55 seconds left on the shot clock), which is squarely in the middle of the 15-7s range. So, we can say with some confidence that the shots from the 15-7s range are the most representative of a typical game scenario than any others. The 36% on 4 attempts is quite good given Luka’s on-ball role, and is a number that, on high volume, I would be totally satisfied with long-term (assuming he maintains a similar role, of course). The shot-clock range could even be expanded to 18-4s, when most of Luka’s offense should take place, given that he’s not finishing transition plays; that would give you 35.3% on 6.6 attempts per game. Again, not too bad. (Now just earlier I was preaching about considering the totality of a player’s shot distribution, but this situation differs in a couple of ways. One is that the ‘when’ of a shot versus the ‘where’ of a shot are completely different dynamics, with certain early-clock shots representing poor yet correctable decision-making more than anything else. Two is that I’m looking for context that could be concealing a better shooter/reasonable room for growth, rather than describing his bottom line impact right now). What really drags Luka’s 3P% down is the ritual early-clock (22-18s) three (1.1 per game on 27.9% shooting) and it’s partner in crime, the bail-out shot (4-0s left, 1 per game on 6.9% shooting). Obviously, with the on-ball role that Luka plays for the Mavs, those types of shots are unavoidable from time to time, but I would still expect him to get his % in those situations into the 20-s, at least (Porzingis may be a better option in those scenarios due to his size, but this is about Luka). As a little abstract experiment, if you cut Luka’s 22-18s volume in half and pretend that he makes 25% of his 4-0s shots, then his overall 3P% is 33.5 (on 8.2 3PA), which is at the very least nice to look at, as it clears the 1 PPS mark, and is also a good estimate of what Luka’s 3P% would actually look like with a teensy bit of improved shot-selection and some regression to the mean late in the clock. However, just to note, Luka’s 2018-19 numbers, for what they’re worth, are basically inverted, with Luka shooting 29.8% in the 15-7s range and hovering around 40% everywhere else. It looks like this:

His rookie year splits, however, include the first half of the season where he didn’t occupy the same ball-dominant role he does now.

Now, let’s discuss some other potential indicators of shooting ability. First off, Luka is still very young; with the pandemic and all, it’s entirely possible that he’s never been in an American bar, so I don’t think that it’s entirely unreasonable to look at him in part as a draft prospect (something which I completely inexperienced doing, to be clear). Two very good starting points are FT% and volume, with some game context sprinkled on top. Going back to his final year in Europe, between both FIBA and domestic play, Luka shot 80% from the line on 306 total attempts. So far in the NBA, he’s made 73.7% of his 1047 attempts, with a 71.3% -> 75.8% jump from year-one to year-two. However, according to the projection tool DARKO, there’s been no consistent positive trend in Luka’s shooting, both from the FT line and behind the arc. Now as for volume/context, Luka certainly checks a lot of the boxes. As previously mentioned, he has very high volume paired with a league-leading UAST% on 3’s, so he already possesses the shooting tools that are arguably harder to learn, that being shooting off-the-dribble in every scenario imaginable. The brightest spot here is that Luka already has a step-back anchored by outstanding footwork, which can effectively serve as a catalyst for any improvements to his shot.

As you can see, his funky inside-out movement ultimately creates space for him to fire off good shots, and the ability to create separation isn’t going anywhere. Another little positive is that Luka is really more Harden than LeBron, aka his shooting isn’t handicapped by otherworldly athleticism that makes it hard for guys like LeBron and Russ to get mechanically sound and effective shots. What I hope to have highlighted is that despite the unflattering numbers on the surface, Luka’s shooting is much farther along than it may seem.

Room For Improvement

Luka is really good as is, but there are always ways to get better. I’ll try to avoid suggestions like ‘jump higher’ or ‘make more shots’, because then I’d be wasting your time. Rather, I’ll focus on areas that merely need tweaking through more attention to detail (although he should definitely be focusing on his three point shot). First up is:

Better Decision-Making out of Step-Backs

After watching a good chunk of them, Luka’s step-back may have become my favorite in the league due to the way that he manipulates his defender and creates separation with his counter-heavy, paced dribbles. His step-back involves some side-to-side displacement as well, so that when the defender recovers and scrambles back to contest his shot, they do so with their body turned completely sideways, and one hand contesting the shot. Their extremely pronounced one-foot-forward stance makes almost every close-out vulnerable to a second cross and a drive to the hole. Look at the two clips below, both against the same player, to see what I’m talking about:

In both clips, Luka modestly attacks, selling Josh Jackson, who fully commits to the drive like he’s on the end of a yo-yo. Then, again in both clips, Luka steps back (with a cross), and Jackson, whose momentum is still carrying him backward, is stuck playing catch-up, and has to (or does, at least) close out hard, both times with his right in front of his left. While Luka’s a bit farther back in the first clip, that shouldn’t matter. In both scenarios, Luka has the ball in his left hand while Jackson is closing out with his right foot out front; the defender is already set up, facing the wrong way, and all Luka needs to do is dribble forward. He settles for a 3 in the first clip, but attacks in the second one. In my opinion, both of those scenarios can and should be rim attacks; the defense is conceding an opening, so take it! Although I talked about why his shooting is better than it may seem, a Luka Doncic step-back 3 is the floor of your offense, not the ceiling. What if I told you the possession below…

…ends like this:

As much as he likes the step-back, it makes no sense to shoot with a lane right in front of you. There is no absolute here; sometimes he makes the right play, and sometimes he doesn’t. It’s just something that needs some tidying up. Ultimately though, for a basketball genius like Luka, I don’t have a hard time believing he’ll improve in this area.

The Two Types Of Floaters (and which one to work on)

As the header gave away, Luka has two different types of floaters, and one of them needs work. As I’ve detailed above, Luka’s floaters, or more generally one-hand touch shots, are an important part of his arsenal against suffocating defenders. He’s all too comfortable delaying/slowing his release, waiting for the contest to pass, and then releasing his shot once a reasonable window opens. It looks like this:

or like this:

or like this:

The key feature that should stand out from these three floaters is the little hitch before the release. Notice how he brings the ball to its apex, only to bring it back down a little, before eventually restoring it to the apex and releasing it. The delayed, hitched release of the ball is in sync with his overall movement, where he suddenly stops his drive before rising straight up and releasing the ball once his defender has fallen backward; I’ve discussed and demonstrated this already, as it’s a fantastic, high-level skill. The off-beat rhythm he uses to beat defenders is second nature to him, and that’s the problem. When Luka actually has some breathing room, he frequently fails to adjust, and all too often ends up launching some weird hybrid shot rather than the quickfire floater he should get up. That befuddlement/hesitation looks like this:

This looks like a glitch in the Matrix. Notice how when Luka first gets into the pocket of space between Danny Green and Javale McGee, he initially brings up the ball as if to shoot it, but then puts it back down, finishes his drive, finds out he’s in McGee’s face, and gets blocked. In this scenario, the defense was initially out of place, and extending the drive was counter-intuitive here; Luka already had space, he just needed to use it. A similar blunder takes place below:

In this clip, a disinterested AD can be counted out. Luka stops and fires into space, but as you can see, he’s very out of rhythm. He needlessly double-clutches on his shot when he should really just go up in one quick, smooth fire. So, uh, what does this special floater I’m referring to look actually look like? Well, I found one (after some digging). Check it out:

I hope you saw what I was talking about. Luka recognizes the space, stops, and fires quickly in a single, smooth motion. From a non-Luka perspective, what stands out the most from this play is the chaos and almost transition-like atmosphere. I think that the frantic and uncontrollable pace of the play is what took Luka out of his usual rhythm and caused him to shoot the floater the way he did; there’s nothing Luka-like about the floater at all. THIS is what he needs to practice, and not only getting comfortable with using it, but also getting better at feeling when to deploy it. Looking for example at the play below,

and you see that Luka released his shot just a millisecond too late (watch it again if he still seemed totally in sync). In this case, due to the nature (back-rim) of the miss, a slightly quicker release would have done the job. Rather than looking at the play purely through hindsight, reverse your thought process; the ball is released by a player on a forward trajectory a bit too late, and as a result travels a little farther than it should. Next is a more pronounced example, one that shows his underperforming quickfire floater almost in a vacuum:

On this possession, the amount of space Luka got (he probably never sees that much) gives him a blank canvas to showcase the type of floater I’ve been describing. It looks pretty good, but there’s still some awkwardness to it. The last dribble he takes is debatable, and his body and shot don’t seem to be in sync the way they usually are. Although I wasn’t strictly keeping track, from the clips I watched (FGA between 5-10 feet, inclusive), my unreliable human brain tells me that he was much more efficient when shooting his hitched floater, despite them usually being more contested, as that’s what calls for their use; in my estimation, it’s the consistent rhythm demanded by the hitched floater that makes Luka shoot better on them, a rhythm which he lacks on more open floaters. A little preview of what this might look like is here:

This is one of the scenarios when Luka would ideally use a quick-release floater, and he does! This is probably the most in-sync one I’ve seen yet, which I think is helped by him getting to take two meaningful steps and OG’s positioning at the rim demanding a quick decision (ironically, I could see a hitched floater working here as well, but it would probably be a tougher shot). Despite these clips being a rarity, the glimpses here and there are all I need to believe that a quick-release floater is well within the realm of possibility.

So in conclusion, Luka is a good scorer. This was by far my deepest and most time-consuming piece yet, and I’d really appreciate a share on Twitter, assuming you enjoyed it, of course. However, if you didn’t, then go and show it to your friends so you can all laugh about how bad it was together. Free press is free press.